Racist History

About The Project

Racism in the U.S. Health System: The Transformation We Need analyzes structural racism across the U.S. health system and how to dismantle it through collective leadership across the health sector and beyond. Grounded in deep consultation from patients, advocates, leaders, and others, these strategies support anyone seeking to strategically lead structural change to move toward a more just, equitable, and inclusive health system.

More About the ProjectFor 50 years, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) has invested in the leadership of clinicians. As the nation continues to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic and grapple with its long history of racial inequity, the Foundation is continuing to discover how to best support clinicians in dismantling structural racism in the U.S. health system.

We engaged CoCreative to lead a unique eight-month consultative process. They asked more than 230 diverse health system constitutents to share their insights about the current system of racial inequities, to develop a compelling vision of the system we should strive for, and to share their views on the structural shifts needed to realize that vision. This report reflects their collective thinking.

Coming face-to-face with the complexity and scope of structural racism within our nation’s health system made it clear that our approach to leadership needs to evolve. RWJF now sees how leadership committed to tackling structural racism is required across the entire health system, not only from clinicians and healthcare leaders. Through this work, we have clearly heard that we all need new ways of working together, particularly the capacity to lead collectively across organizational, sectoral, political, and cultural boundaries.

While this research project was focused on informing the design of the next evolution of one of RWJF’s flagship leadership programs, we share an overview of the findings here as information for our allies in the larger field.

Like so many of you reading about this work, we here at the Foundation are in the process of learning about the complex changes necessary to undo the centuries of harm wrought by racism. We appreciate the insights into the impacts of racism on healthcare that CoCreative’s work has surfaced. We are just beginning to dig into what they have learned, and to have conversations about what our role should and can be going forward. This challenge is daunting, but we know facing it head-on is now more crucial than ever.

We hope you’ll join us in considering what role you can play in helping our nation make the shifts necessary to make the health system a powerful platform for change, lighting the way toward true wellness and a more just society for all.

Section 01

“A system where love runs throughout.”

– consultation session participant

Throughout this process, the research team asked leaders to share their hopes and aspirations for our nation’s health system . What do they most want to see? What kind of system should we, collectively and individually, work toward? Those visions shared one clear, common thread: the nation needs a health system that is grounded in our humanity, that treats the people who work within it humanely, and serves all of us as whole people.

In imagining a more just health system, stakeholders highlighted words like “love,” “justice” and “spirit” that aren’t often part of conversations about systems change. We were struck that words such as these shouldn’t be considered radical or outside the “real” discourse of health. These words, in fact, became central to the vision that emerged:

A racially just and equitable health system grounded in love and belonging that treats people with dignity, provides culturally excellent high-quality care, and enhances the well-being and quality of life for all people.

That vision also contained within it sadness and frustration, as it is painfully clear that some stand far from this vision. If one is poor, Black, Latinx, or Indigenous in our country, the health system systematically fails to provide high-quality care. It’s hard for many to have faith that a new reality is even possible.

The path forward lies in accepting, fully and honestly, the reality of pervasive racism across our health system and committing to a transformational, anti-racist agenda for change. While this work is explicitly about taking on racial inequities, the same strategies will create a system that works better for all.

Section 02

“We all are actors in this process, and carry water for these systems that harm us and exclude us.”

– Theresa Trujillo, project Advisory Team member

No system, whether it’s a system of education, agriculture, or health, exists in isolation. Each of these systems is deeply embedded in the cultural, political, and economic context of our country. As is shared across this analysis, researchers found that the design of the health system reflects a set of dominant beliefs in our society, in particular:

An embrace of individualism. If you’re not healthy in this country, the system and those within it will tend to blame you as an individual for the “choices that you’ve made” that have led to your health situation. Even lack of access to care reflects this bias: “When we choose not to help people, we’re ultimately blaming them for their choices,” one leader noted.

An embrace of individualism. If you’re not healthy in this country, the system and those within it will tend to blame you as an individual for the “choices that you’ve made” that have led to your health situation. Even lack of access to care reflects this bias: “When we choose not to help people, we’re ultimately blaming them for their choices,” one leader noted. The combination of these beliefs form the basis of a harmful, self-reinforcing dynamic:

These beliefs have convinced us to accept a national health system in which healthcare providers make more money when people are sicker, where BIPOC people are systematically sicker and dying faster based solely on the social construct of race, and where people hold little hope of changing the system despite few people being satisfied with how it operates.

To more clearly convey how the health system operates, CoCreative synthesized insights from health leaders to develop maps that depict how health equity is undermined by societal beliefs. The maps were reviewed and refined by the project’s Advisory Team.

Given the mutual interdependence of these driving beliefs and the realities of our current health system, we must realistically talk about changing both our health system and the context in which it operates? Otherwise, any efforts to change our health system will be undermined by the larger political, social, and economic context in which it operates.

Our health system is both economically influential and plays a unique role within our society, making it a powerful platform for larger societal change. By grounding our health system in its purpose of care, health, and wellbeing, we collectively have a powerful leverage point for shifting the larger culture and the systems that support health. The health system is full of caring, compassionate people who want good health for themselves and others. It also has resources which, although unevenly distributed and heavily concentrated in healthcare in particular, are nearly unparalleled in our economy. The many people we consulted believed that the health system can lead, model, and create a vision of what’s possible and show the way to a more equitable, just, and healthy society.

To ground this inquiry in the lived experiences of people within and around the health system, CoCreative conducted 61 in-depth interviews with health system stakeholders, both those who are in positions to most impact health outcomes and those who are most impacted by disparate outcomes based on race.

There were also six open consultation sessions with an additional 150 health system stakeholders and patients. Additionally, a six-person Advisory Team reviewed and helped deepen and extend the structural analysis. The following 10 key themes emerged from this consultation process. Learn more about the consultation methodology.

With racial equity a more urgent national priority, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation wanted to hear from leaders about what it would take to dismantle structural racism in the health system . And, how we could create a better system, grounded in equity, that works better for everyone.

More than 200 health leaders spoke to these questions through an 8-month collaborative process led by CoCreative. To more clearly explain how racism fuels health disparities, CoCreative synthesized the insights of health leaders and developed this map.

Let’s start with access to resources. Good health is closely connected to where we live. Research has shown that we enjoy longer, healthier lives when we have access to the drivers of good health, like quality housing, healthy food, good schools, and reliable transportation.

But in the U.S., access to quality resources like safe housing largely depends on a person’s earning power. Without good-paying jobs, people have less income and wealth, and can’t afford to live in resource-rich neighborhoods.

Likewise, lower access to these resources also determines people’s earning power. This dynamic forms a vicious, self-reinforcing cycle that has undermined health and opportunity for lower-income families for generations.

But it’s not only about economics. For decades, for example, redlining and housing segregation have kept people of color out of well-resourced neighborhoods. Too often, people of color can only afford to live in communities with unsafe housing, under-invested schools, poor quality healthcare, and few fresh food options.

There’s a long history of denying people of color equitable access to resources and opportunities, starting with the extraction of wealth and land from indigenous people and continuing to slavery. That legacy of racism shows up today in job discrimination, lack of capital for BIPOC-owned businesses, the system of mass incarceration that disproportionately targets and harms people of color, and in many other areas.

And these factors impact not just one generation, but multiple generations, also showing up as intergenerational disadvantage and trauma that’s associated with poorer health and shorter lives for people of color.

The health care system has reinforced these cycles. Institutional investment policies, hiring practices, and procurement policies that drive and reinforce gentrification, low-wage jobs, and concentration of wealth in white communities deepen the impacts of structural racism. At the same time, some health systems are now starting to leverage their economic assets as positive forces to address racial disparities, a powerful force for equity given that health care is so economically powerful, employing 11% of American workers and accounting for 24% of government spending.

Health care, however, is also dominated by white administrators and doctors who are trained in medical schools that reinforce racist beliefs and practices. Racism in medical admissions and educational access is another barrier that results in the health workforce not mirroring the communities they serve.

And when people of color receive worse care because doctors are biased, or make flawed assessments due to racist diagnostic tools, it’s easy to understand why BIPOC have lost trust in the health system, making it less likely they will participate in clinical trials or trust new or existing medical treatments, therefore worsening health outcomes.

As we look at the big picture, all of these dynamics work together to undermine the health and well-being of people of color and other systematically disadvantaged people.

These dynamics do not only impact people of color, however, because many of the solutions to improve these dynamics will also support better health for all Americans. Take the example of curb cuts. Because street corners used to have curbs that made it difficult for people with disabilities to move between sidewalks and crosswalks, disability activists created and then fought for curb cuts. It soon became clear, however, that so many more people benefit from this solution, like people using strollers, skateboarders, people who have trouble with their legs, or people using carts to carry groceries home. So if we design our health system to include and take care of the widest diversity of people, then we all benefit.

Section 03

“Disparities don’t naturally grow on trees. They don’t naturally appear in nature…Anything that’s been socially constructed can be socially deconstructed.”

– Michellene Davis, project Advisory Team member

The research team asked leaders across the health system to identify the most critical shifts needed to move toward the vision they had expressed for equitable health in this country:

A racially just and equitable health system grounded in love and belonging that treats people with dignity, provides culturally excellent high-quality care, and enhances the well-being and quality of life for all people.

The shifts below attempt to synthesize the feedback from these health leaders on the “problem spaces” where they believe health system leaders might focus their efforts for greatest impact. They are not about HOW to create change but WHAT PARTS of the system most need to change in order to make the vision a reality. Most importantly for this inquiry, these shifts have informed researchers about the kind of leadership the health system really needs, and where. As you review the shifts, you may get a sense that they imply a different level of leadership (beyond institutional-level change), more diverse leadership, and different ways of approaching change across organizational and sectoral boundaries than has been employed in the past.

Some of these shifts may seem daunting and reasonably raise skepticism. The research did not specifically look at what is feasible at this point, because feasibility often leads to transactional, marginal, and short-sighted interventions. Instead, we wanted to know what leaders identified as aspects of this system that most need to change, no matter how difficult the change or how long that change might take. Some shifts may take years, while others will take generations. This is the nature of the structural change that is required to achieve the vision.

Finally, this list of the 14 most-needed structural shifts is shared with the caveat that, while this research project is finished, the learning and evolution of our research team’s thinking is not. This set of shifts will necessarily evolve as the work continues to deepen a shared understanding of where the most powerful opportunities for structural change in our health system lie.

Confronting our Racist Reality | ||

|---|---|---|

| Current State | Future State | |

| Lack of Accounting for Racist Past | We have not reconciled the deep history of racism that is still embedded in today’s health system. | Key institutions across the health system are actively engaged in a meaningful process of truth and reconciliation around past and present racism in their systems. |

| Certain Bodies Cherished More | White, male, cisgendered, and nondisabled health and wellbeing are consistently valued over the lives of BIPOC, women, transgender, and disabled people. | We have a shared culture of health in which all lives are valued equally. |

Profit Over Purpose | ||

|---|---|---|

| Current State | Future State | |

| Capitalist Basis of the U.S. Health System | Much of the U.S. health system is increasingly driven by capitalist mentality and values. The system prioritizes profit maximization | We have effectively disconnected the U.S. health system from the capitalist economic system and grounded it in a social purpose of health and well-being for all. |

| Treatment- focused Payment Models | Payment models and systems incentivize efficient delivery of high volumes of services that favor treating disease over nurturing wellness. | We have structured all major payment programs to center disease prevention and well-being and incentivize equitable outcomes around race. |

| Current State | Future State | |

|---|---|---|

| Burden on BIPOC Leaders | Anti-racism healthcare leaders experience racial battle fatigue, are often marginalized to the fringes of the health system, and their recommendations are mediated by white cultural norms. | BIPOC leading systemic changes to dismantle structural racism in healthcare are fully supported in their well-being, resilience, and capacity and their work is valued and centered within the health system. White co-conspirators step up with a spirit of co-design and shared leadership, seeing that this is everyone’s work. |

| BIPOC Health System Workforce Inclusion, Agency & Power | BIPOC are largely excluded in health system leadership and clinical positions and BIPOC across all health system positions are poorly supported. BIPOC feel silenced, neglected, or discarded in our healthcare system. | BIPOC are included across all levels and functions, particularly senior leadership and clinical care, and experience a culture of belonging that lends agency and power to their work. |

| BIPOC Patient Voices Discarded | BIPOC patients are not listened to and are treated as people without agency or a say in their own health decisions. | The goals, aspirations, and priorities of BIPOC patients are centered in decisions about their treatment and care. |

| Current State | Future State | |

|---|---|---|

| Anti-Racism in Health Professional Education | Health professionals lack understanding of the structural and racial determinants of health, and they in fact gain racial and gender bias during their training. | The awareness and behaviors of all clinicians, researchers, and health professionals are aligned with racial justice. |

| Current State | Future State | |

|---|---|---|

| Racism and Racial Bias in Research & Diagnostics | Unfounded race-based (and sex-based) distinctions are endemic in medical research, diagnostic standards, and testing technologies. | We have eliminated unfounded race and sex-based distinctions in research, diagnostic standards and testing technologies. |

| Racism’s Role in Outcomes Not Being Measured | A majority of the U.S. health system is unable to identify the role that racism plays in patient and community health outcomes. | The use of disaggregated data to close race-based gaps in health outcomes is standard practice across the health system. |

A Focus on Community | ||

|---|---|---|

| Current State | Future State | |

| Undermined Public Health System | The U.S. public health system is underfunded and under threat. | We have an effective, well-funded public health system across the country that’s led by public health professionals and grounded in equity. |

| Accountability to Communities | The U.S. healthcare system is increasingly centralized and consolidated, separating it further from community focus and accountability. | Our health system is organized around the needs and priorities of communities, especially those most underserved, with clear accountability to, and shared governance with, those communities. |

| Current State | Future State | |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-System Approach to Structural Drivers of Health | Our health system heavily focuses resources, expertise, and capacity on treating downstream outcomes to the neglect of shifting the upstream, structural drivers of health. | Leaders across the health system actively partner with leaders from other sectors to change culture, policies, and investments to build new equitable systems (e.g. housing, community safety, policing, education.) |

| Complete Health and Wellness | The U.S. health system is fragmented and heavily focused on the treatment of illness and symptoms of disease. | Our health system is employing a proactive, holistic, and culturally excellent approach to health and well-being. |

If there is one overriding theme that emerged from this consultation process, it’s that taking on the kinds of deep structural shifts needed to dismantle structural racism and design an equitable health system requires a different kind of leadership than what currently exists or is typically rewarded. While people came from different traditions and experiences in imagining what this kind of leadership might look like, there was general agreement that (1) we haven’t seen enough of it, (2) the people who do it are often under-resourced, and (3) conventional approaches to leadership fall short of what’s needed for structural change.

Current strategies have made little progress in dismantling structural racism. Despite years of highlighting racial disparities in health outcomes and multiple studies and initiatives, disparities have worsened in many areas, from life expectancy to organ transplants to social drivers of health like income and household wealth.

Study after study show that one of the biggest challenges in taking on structural racism is that our nation’s system of health is embedded in deeply held beliefs about the primacy of individualism, the unassailable power of capitalism, an assumption of scarcity and a zero-sum game, and, most deeply, a hierarchy of human value. It’s the last of these in particular that informs decisions about not only who receives treatments and who doesn’t, but whose voices are at the table, and listened to, when decisions affecting the health of communities are being made.

Dismantling structural racism requires an understanding of how these deeply held beliefs operate, as highlighted in these key insights from health leaders:

If leaders don’t believe that racism exists or matters, or if it threatens their own status, they will marginalize efforts to address it.

Racism plays out at every level of the health system and every level of society, and any effort to dismantle it must be multi-dimensional.

Racism blinds us to the opportunity to build a health system that is better for all.

Section 04

“We need leadership that welcomes and values diversity in all forms so that people from both privileged and less resourced backgrounds can come together, realizing that we are actually all interconnected, and find a collective purpose that moves health leaders out of silos.”

– consultation session participant

One of the challenges of advancing leadership to dismantle structural racism is that dominant cultural norms shape our views and beliefs in deep and persistent ways, including how we even think of leadership itself. For many, the only image of leadership is of people with positional power doing “leaderly” things, while others more or less follow them. Whether we believe great leaders are born, develop leaderly traits over time, adapt their leadership approach contingent on the situation, or just behave in leaderly ways, our dominant picture of leadership is still deeply individualistic.

That picture of individual, heroic leaders commanding and controlling others is so embedded in our culture, and in the healthcare sector in particular, that it keeps upending meaningful conversations about the kind of leadership we actually need.

That’s a problem because structural change requires collective leadership—leadership that emerges among diverse people who commit to one another and to a common cause, where people not only work effectively across their differences, but leverage those differences as sources of innovation and resilience; where they develop a shared structural analysis and powerful shared strategies; and where they lead together with mutual accountability across and between organizational, sectoral, and even political boundaries to change the deep structures around them.

To ensure that we’re working from the same understanding of “leadership ,” we first share this working definition that emerged from our Advisory Team and through our consultations:

Leadership is a collective, relational process

whereby individuals move themselves and others

through practices of discernment, growth, and change

to achieve health equity with and for those that our systems have pushed to the margins.

We should note that this picture of collective leadership doesn’t mean that we don’t need individual leadership. Collective change requires leaders who are willing and able to create and hold spaces where everyone involved can bring their diverse experiences, capacities, and approaches and work together toward a common vision.

Taking on structural racism in our health system requires a diverse range of capacities that no single person or organization, no matter how large, can provide. One leader noted, “We need people who are contributing in diverse ways to address the issue: people focused on disrupting and deconstructing current systems, people who are envisioning the way new systems could operate, people who are identifying transitional strategies.”

Based on the interviews we’ve conducted and the many accomplished leaders we spoke with, the research team believes that much of the necessary knowledge, skills, and abilities needed to dismantle structural racism already exists across our health system. That capacity is not being leveraged, however, in part because of lack of resources for collective leadership approaches, in part because many people who hold these abilities are marginalized by the system, and in part because the spaces often don’t exist for that collective work to happen.

Given this, we collectively need to expand our focus from developing and supporting individual leaders to developing and supporting spaces in which diverse leaders can lead together—what we’ll call here Collective Leadership Spaces. These are spaces that are created when people who have a stake in changing a complex system, whether our national health system or a local community health system, organize to change that system.

As researchers asked stakeholders across the health system about the leadership we need to dismantle structural racism, they described what a powerful collective leadership space looks like.

At their core, collective leadership spaces are made up of people who are deeply committed to structural change, regardless of their positional power or formal authority. Too often, leaders with positional power in the health system are convened to determine the vision, analyze the system, and determine priorities, when these leaders are invested in how the system is now. We instead need diverse leaders who are committed to deep systemic change and will build the power they need, engaging positional leaders over time in an ambitious agenda for change.

They comprise whoever is needed to do the work across organizational, sectoral, political, and cultural boundaries. While many people we spoke with focused on dismantling racism inside our individual institutions, others noted that won’t be enough to address the kind of structural shifts that are needed. As one leader put it, “A multi-stakeholder, multi-sector conversation and process is needed for systemic transformation. It should include all sectors, not only healthcare, but groups in transportation, human services, the private sector, philanthropy, the public sector. Then we can have a conversation about how we are going to structurally improve health outcomes.”

Within effective collective leadership spaces, these attributes and behaviors are essential:

One of the common refrains from leaders is that the work of organizing and convening these spaces is important but undervalued and under-resourced. While some funders have increased support for collective leadership spaces, more is needed. “It’s really going to take collaborative partnerships that are given the resources and the authority to work together in a way that really addresses what we know are the real root causes,” one leader said.

Convening and supporting collective leadership spaces—what Beverly Wenger-Trayner and Étienne Wenger have termed “systems convening”1—also requires specific capabilities. As one leader noted, “We can’t just throw people in a room and hope they figure it out. We need people with the ability to support these kinds of processes. Without those skills, these collective efforts can sometimes be a mess.”

Some of the core “collective leadership convening” skills identified by leaders we spoke with are the ability to:

“Systems Convening: A crucial form of leadership for the 21st century” by Etienne and Beverly Wenger-Trayner

Finally, leaders also shared specific commitments that they believe are important for anyone engaging in this work to take on, most notably:

An overview of the landscape of current programs supporting leadership development at the intersection of health and structural racism.

As CoCreative consulted many stakeholders across the health system about the leadership we need to dismantle structural racism in the U.S. health system, we also surveyed the landscape of programs focused on that challenge. We wanted to ensure that any new RWJF program developed based on our learnings should complement, not duplicate, existing offerings in the field and/or potentially build on programs that are already meeting the needs that leaders identified through this inquiry.

We summarize our findings here and offer profiles of the top programs below for those who want to learn more.

First, many current programs are making strong contributions around aspects of collective leadership: advocacy, organizing, and civic engagement; narrative change; racism, oppression, and discrimination; and antiracist, equity-centered leadership. Some of the programs engaged participants in understanding the history of oppression and how BIPOC have been harmed by our health system and the institutions within it and in building the skills needed to support healing from that history, and many leaders we spoke with identified these both as important elements.

However, many programs appear to underemphasize systems change capacities—seeing the whole system and the dynamics driving it, convening and supporting people to work across organizational and sectoral boundaries, working across all levels of the system, identifying high-leverage structural intervention points, and advancing multiple concurrent interventions to address different points. This implies that a program that supports these capacities might contribute something both new and needed in the field.

We also observed that the choice of delivery partner for leadership programs also influences the design and accessibility of the programs. For example, programs offered by universities were often limited to enrolled students and may also be influenced by the racism and power differentials in the university structure and culture. We were curious then about how programs could be funded, designed, and delivered by a diverse group of funders, curriculum creators, and facilitators with fewer institutional constraints.

We also examined whom the programs are designed for and found that most programs began the selection process with who would be a fit for the program’s leadership learning focus, rather than asking what areas of structural change needed work and then identifying who is ready and willing to advance change in those areas.

As we spoke with health system stakeholders about what a new kind of leadership program might look like, a number of program “design tensions” emerged. While these tensions could be perceived as either-or choices or possibly spectrums of choice, we believe that they are most powerfully conceived as tensions to leverage in advancing a more holistic approach to leadership. We looked at the existing landscape of programs through this “polarities” lens to see where the field might be out of balance in its approaches.

| Design Tension | Implications for Program Design Choices |

|---|---|

| Learning & Doing the Work | Throughout this inquiry, we’ve heard a recurrent theme that the most powerful way to develop as leaders is to learn by doing and applying learning to real-world work. More and more leadership programs are striving to include action-based learning as a strategy for making the learning applicable to real life situations. At the same time, whereas programs typically invite participants to work on their projects in the context of the learning experience, we believe that flipping that orientation and embedding the learning into the work instead might be a more effective way to leverage this tension. |

| Individual & Collective Leadership | We also heard that while individual leadership is important, it’s simply not sufficient for tackling deep structural challenges. Some leadership programs, including RWJF’s former Clinical Scholars program (note, RWJF funded this research), have expanded participation from individuals to small teams. We believe that we can extend that further by integrating support (in the form of peer sessions, coaching, and targeted training) for individuals even as they engage deeply in collective leadership work. |

| Aligned Priorities & Decentralized Leadership | While there are many efforts to address structural racism in the health system, our community lacks a coherent, system-level analysis within which we can support diverse leadership and approaches toward shared priorities. With most programs, participants are encouraged to work on a project related to addressing health equity in their organization or community. We believe that supporting leaders to come together and work on system-level priorities (e.g. the system shifts identified through this process) and learning in the context of their collective work will be a powerful contribution to the field. |

| Supporting BIPOC Leaders & Engaging White Leaders | While many BIPOC already working on dismantling structural racism in the health system desire support to continue difficult and often painful work, we also heard a clear desire to engage more leaders—especially white co-conspirators. Many programs, especially since 2020, have prioritized participation of BIPOC leaders. While that’s important, we suggest that from a systems change perspective and to avoid deepening the burden for anti-racist leadership on BIPOC, we need programs that actively engage white partners in this work as well. |

| Partners determine learning & Participants determine learning | We also heard diverse and sometimes competing views on the question of who should determine the content of any leadershipprogram. From one perspective, we have organizations with deep expertise in helping people develop their leadership capacities. From another perspective, participants themselves are the experts on what they most need to lead more effectively. On top of that tension, structural change work will require experimentation and even failures so neither the pathways of work or the learning agenda can be fully determined ahead of time. That said, we heard from several programs that they are shifting from a set program designed and determined by the delivering organization to a dynamic program design that evolves based on direct, even real-time, guidance from program participants. |

In 2021 and 2022 in particular, a number of new leadership programs have emerged that are aimed at addressing structural racism and health inequities in health and the healthcare systems. Several foundations, institutions, and networks have either redesigned existing programs or formed new programs to better meet the demands of this leadership challenge. Our researchers identified the following leadership programs that are centered on racial and gender equity in health or healthcare, and/or dismantling structural racism in health or healthcare.

The Culture of Health Leadership Institute for Racial Healing (CoHLI) is an 18-month leadership experience developed by the National Collaborative of Health Equity in partnership with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The Culture of Health Leadership Institute for Racial Healing was designed over an 18 month period utilizing a design team, input from the field, and curriculum developers and will launch its first cohort of 40 individuals in May 2022. The CoHLI uses the Truth, Racial Health and Transformation (TRHT) framework to strengthen ecosystems of practitioners who are advancing racial and health equity.

The institute seeks to build a nationwide network of health and racial equity practitioners by providing tools and resources to hold public and private sector leaders accountable for progress. The CoHLI seeks to bring together practitioners already working to address one or more of the pillars in the TRHT framework. The institute seeks to work with practitioners who want to collaborate across a national community of practice to build a Culture of Health.

Diverse Executives Leading in Public Health. In 2021, The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) and the Satcher Health Leadership Institute (SHLI) at Morehouse School of Medicine launched a new 12-month leadership program entitled, Diverse Executives Leading in Public Health (DELPH). DELPH received its initial funding from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

DELPH is committed to preparing mid-to-senior-level government public health professionals and ensuring that the workforce reflects the diversity of the jurisdictions they serve. DELPH aims to “increase and strengthen participants’ visibility and exposure within public health systems, and access key networks and leadership development opportunities.” (ASTHO). DELPH recruits 15 public health professionals from underrepresented groups.

Health Equity & Social Justice Leadership Program (HESJLP) is a 4-year academic fellowship program at Rush University. The HESJLP seeks to “empower medical students with the knowledge, skills, and experiences that they can use to advocate for health equity throughout their careers.” (Rush) Through this program, medical students are given the opportunity to receive in-depth education and enhanced clinical training and experiences focused on global and local health equity and social justice.

The HESJLP recruits 20, first-year medical students who participate in a variety of experiences geared towards a career focused on vulnerable populations, health equity and global health.

Medical Justice in Advocacy Fellowship launched in 2021 and is a program of the American Medical Association and the Satcher Health Leadership Institute at Morehouse School of Medicine. “The inaugural Medical Justice in Advocacy Fellowship is a collaborative educational initiative to empower physician-led advocacy that advances equity and removes barriers to optimal health for marginalized people and communities.” (AMA)

The MJAF is designed for 12 physicians and residents who have a demonstrated interest in health equity and advocacy. This post-doctoral program is designed to enhance physicians’ advocacy leadership skills to improve health outcomes and advance health equity. The MAJF uses a “anti-racist, equity-centered learning framework”, mentoring and a training platform to provide skills, tools, and knowledge to engage in institutional and political health advocacy.

The Racial and Economic Equity Awareness and Leadership (REAL) series launched in 2021 and is a cohort-based initiative open to members of the Healthcare Anchor Network, a multi-stakeholder collaboration of 71 health systems advancing racial and economic equity in the communities they serve.

With support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the REAL series is designed to enable healthcare leaders to understand and cultivate the systemic leadership capacities needed to advance racial and economic health equity within organizations and society at large. The first two cohorts focused on individual leaders committed to convening work to address racism in the economic determinants of health and a third cohort will invite teams of leaders to work on a specific racial and economic equity challenge together.

The Equity Collaborative, sponsored by the Carol Emmott Foundation, is a learning community of leading healthcare organizations committed to inclusive gender equity within their organizations and across the country. In 2019, The Equity Collaborative launched to accelerate progress in achieving institutional gender equity and promoting gender equity across healthcare. The goal of the Collaborative is to “demonstrate how fully inclusive gender equity improves organizational performance, including employment engagement, patient satisfaction and health outcomes, and reduces healthcare disparities.” (Equity Collaborative)

Healthcare and healthcare-related organizations with a large employment base are the target population for the Collaborative, which helps healthcare organizations transform their culture to accelerate the advancement of women in senior management and governance. The Collaborative brings together large healthcare systems to make a 3-year commitment to work together and share best practices to enhance fully inclusive gender equity within their institution. There are currently 14 members in the Equity Collaborative in both medical and academic settings.

In 2016, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation launched Truth, Racial Healing & Transformation (TRHT), as a comprehensive, national and community-based process to plan for and bring about transformational and sustainable change, and to address the historic and contemporary effects of racism in the United States.

The Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation Framework and Implementation Guidebook was co-developed by 176 leaders and scholars from more than 144 national TRHT individual and organizational partners. TRHT aims to help communities embrace racial healing and uproot the conscious and unconscious beliefs in a hierarchy of human value. The TRHT framework is an adaptation of Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) models and is focused on healing and truth telling “to jettison the belief in racial hierarchy.”

In 2017, WKKF invested $24 million into 14 places around the United States that were pursuing racial healing and using racial healing circles to catalyze their transformational work. (TRHT). TRHT places are in their 5th year of implementation.

RWJF also funds and/or sponsors a number of leadership development and related programs. Leadership for Better Health is the RWJF focus area that concentrates on leadership development programs that “supports and connects change leaders nationwide who are working to build a Culture of Health.” Examples include:

| Program | Target Population | Format | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture of Health Leaders | Leaders from diverse groups who want to advance health and equity | Individuals | |

Culture of Health Leaders (COHL) was a 3-year leadership development opportunity for people working in every field and profession who wanted to use their influence to advance health and equity. Through this program, leaders were prepared to collaborate and provide transformative leadership to address health equity in their communities. COHL is a RWJF collaboration with the National Collaboration for Health Equity, CommonHealth Action and The Center for Creative Leadership The Culture of Health Leaders represented a diverse group of lifelong learner and risk-takers from a wide range of fields (arts, architecture, business, community development and planning, education, faith/spiritual, health and healthcare, public health, technology, transportation, urban farming, and many others) who worked collaboratively across sectors, disciplines, and professions, and prioritized equity diversity and inclusion. Every year, the COHL program broadened the representation from fields and professions across the private, public, nonprofit and social sectors to build a truly diverse group of leaders. Through the COHL program, leaders across sectors, were given tools to:

|

|||

| Health Policy Research Scholars | Doctoral Students | Individuals | |

Health Policy Research Scholars is a 2-year fellowship for full-time doctoral students who are entering their second year of study and are from populations underrepresented in specific doctoral disciplines and/or historically marginalized backgrounds. The HPRS is in partnership with the John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The HPRS started in 1992 and was designed for doctoral students with research-focused disciplines that can advance a Culture of Health. Past fellows were from economics, political science, psychology, architecture, transportation, sociology, social welfare, and environmental health. Each year the HPRS accepted 40 participants from a variety of academic institutions. Fellows participated in a variety of online activities during the academic year and in-person and/virtual events in the summer, fall and winter. The HPRS was aligned with RWJF’s Culture of Health Action Framework. The program has been evaluated by the University of Michigan, Diversity, Research and Policy Program (DRPP). Evaluative information was not available at the time of this report. |

|||

| Interdisciplinary Research Leaders | Researchers and community partner | Teams | |

Interdisciplinary Research Leaders is a 3-year team-based leadership program for researchers and community partners, including community organizers and advocates. Teams, which include two researchers and a community partner, use applied research to inform and support critical work in communities, to accelerate work and advance health and equity. IRL projects align with and support building a Culture of Health. Over the course of the years the primary focus of the IRL applied research projects evolved to advance health equity and build a Culture of Health. The topics covered over the years included:

|

|||

In addition to programs offered through Leadership for Better Health, RWJF provides grant funding to support leadership development across its other three focus areas. These programs support students, community leaders, clinical leaders, and other champions for health equity, who are building a Culture of Health in a variety of settings. This section includes a brief review of current RWJF funded programs related to the intersection of health and/or healthcare, leadership development, and structural racism, though some programs may not heavily emphasize all three of these.

The Ambassador of Health Equity, a 1-year fellowship program is a joint venture between PolicyLlink and FSG. The program brings together leaders outside of the health field to share ideas and experiences, create new alliances, and collaborate to promote health equity. Ambassadors “align around a vision for housing and health equity, and propel their work collectively toward more power in the housing justice movement. There have been 3 cohorts for this program (2016 – 2017, 2019-2020, 2021 – 2022)

Learn MoreIn 2020, RWJF partnered with IDEO.org the Health Equity Collective (HEC) “to create a space for emergent and existing health equity activists, scholars, and medical practitioners to craft a radical, new vision for health justice and develop prototypes to bring it to life in institutions across the country. The goal was to design an enabling digital environment where changemakers could confidently set new standards of wellness and interrogate systems of oppression through iteration and making.”

The Collective has brought together a diverse group of individuals to develop a shared vision of “healthcare that values all people equally, recognizes and rectifies historical and ongoing injustice, provides resources according to need, and is representative of all the people it serves.” The Collective has identified 14 ways to manifest this change in the real world. The Collective is in process of building out the next steps for this work.

Learn MoreThe Health EquityResearch Learning Collaborative (HER-LC) is a professional network of researchers, public health practitioners, and funders committed to advancing the health equity research field, launched in the summer of 2021. This network will allow both government agencies and private foundations to come together and identify and apply solutions through coordinated, complementary, and synergistic research efforts.

Learn MoreThe RWJF Health Policy Fellows (HPF) program is a non-partisan fellowship for mid-career health professionals, behavioral/social scientists, and others with health and health policy backgrounds. Through the program, which began in 1973, fellows work to formulate national health policy in congressional and executive offices in the nation’s capital. Fellows use leadership experience to improve health, health care, health policy and health equity. Fellows participate in an intensive 3.5 month orientation in the fall and are required to make a full-time commitment to the program with a minimum 1 year residency in Washington D.C.

Learn MoreSection 05

How might we design leadership programs that support the collective leadership and collective leadership spaces we need to advance structural change?

While this research was focused on informing the next evolution of one of RWJF’s flagship leadership programs, we share here an overview of our recommendations as information for our allies in the larger field.

It may be clear by now that the design of a leadership program that supports the kind of collective leadership we need is very different from what we’ve seen in the past. It must strategically convene whichever leaders are needed to address the deep structural challenges in the health system, resource those leaders to co-develop and advance strategic interventions, and ground leaders’ learning and development in real action. It must also evolve over time based on what’s most needed to support those doing the work.

Based on equity organizing principles offered by Tatiana Fraser of The Systems Sanctuary, we offer here three principles that would apply to new program development. These principles are designed to avoid the downsides of centralized and ungrounded approaches to capacity building and ensure that any solutions are the best fit for the specific context.

We considered several possible approaches for leadership programs that drive structural change; we recommend a program design that we’re calling “Collective Leadership for Systemic Change.”

Here is a comparison of this type of program versus a more conventional leadership development program:

| Conventional Leadership Development Program | “Collective Leadership for Systemic Change” Program |

|---|---|

| The learning takes space in a learning context (e.g. Zoom or a classroom). | The learning takes place in the context of a real-world collaboration where people are working collectively on a structural racism challenge (e.g. Zoom or a meeting/working venue). |

| Learning and development happens at the individual and small group levels within the learning environment. | Learning and development happens all at levels from the system—from individual to larger systems, because the learning experience is embedded into real-world systems change work. |

| Participants are selected into programs based on their individual leadership potential | Participants are selected to ensure that the group includes diverse and divergent views of the system and different approaches to strategy and change. Educational attainment and professional titles are not the sole, or even primary, criteria for inclusion. Lived experience and community expertise are valued and centered. |

| Participants bring their own issues or challenges to work on in the program; and advance 1-2 interventions or solutions in the organization or community. | Priority structural shifts are identified through a field-wide consultation process, and the stakeholders needed to address these challenges work collectively on agreed-upon structural shifts. Each initiative will develop, test, refine, and advance multiple strategic interventions, possibly including advocacy, training and education, policy change, narrative change, curriculum redesign, market-based strategies, and more. |

| Individuals or small teams apply to participate in the leadership program. | Any organization or group can propose a collective leadership initiative in the priority issue areas. These initiatives could be at any level of the system, from working within a specific community or sector to taking on a national challenge. |

| All participants in a specific program receive basically the same training curriculum and experience. | All participants across all initiatives participate in a foundational training program on structural racism, anti-racist leadership, and systems change leadership. Beyond that, the organization or group supporting the collective leadership initiative, in consultation with the leaders they’ve engaged, determines what curriculum and experience is the best fit for the group’s real-world needs based, for example, on the stage of the group’s work and development. |

| Program participants have access to various custom learning and development supports, ranging from individual coaching to peer learning to training programs. | Initiative participants receive custom learning and development support that they request, from individual coaching to peer learning to training programs. Peer learning and support groups can be BIPOC-only, white-only, or mixed based on the needs of the group. |

| Organizations hosting the initiatives receive little funding for implementation. | The organization hosting the collective leadership initiative (the “backbone organization”) receives funding to support the initiative as well as funds to support the learning and development for participants and their own internal teams. |

| Curriculum may include advocacy, organizing, and civic engagement; narrative change; racism, oppression, and discrimination; and antiracist, equity-centered leadership. | Curriculum may include content at left along with content related to adaptive leadership, systems leadership, and social change leadership. |

| Most learning providers have a core set of principles, values, and agreements that apply to all programs. | All initiatives work at first from a shared set of justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion principles, which might evolve as the groups develop deeper understanding and relationships. |

| Programs operated on a cohort basis, sometimes with light interactions between consecutive cohorts. Cohorts run from 1-3 years. | The initiatives expand and evolve over time, enrolling new/different stakeholders to reflect the evolving strategies and interventions, and operate for as long as needed to address the system shift targeted by stakeholders. |

| Measurement and evaluation is done by a third-party and/or the organization delivering the program, often based on feedback from participants. | Measurement and evaluation is systematically incorporated into the collective leadership initiative, directly involving the participants, the backbone organization, and, where appropriate, a third-party organization. |

In the table below, we assess each program scenario against the program design objectives:

| 1. Individual Transformation | 2. Group Transformation | 3. System Transformation | |

| Centralized Leadership Development Approach | Fairly Strong since the resources for the leadership program are heavily focused on leadership development specifically. | Average since the teams that develop will likely be strong, but they will be relatively small and narrowly focused. | Fairly Weak since the initiatives advanced by individuals or small teams are unlikely to achieve structural change at the larger levels of the health system . |

| Decentralized Leadership Support Approach | Average to Strong with variance based on the specific organizations’ capacities, but would tend toward Strong over time as learning, partner selection, and evaluation deepen. | Average to Fairly Strong, since their organizations would connect like-minded leaders for peer support but they are unlikely to comprise the diversity and expertise needed to address structural challenges. | Average to Fairly Strong depending on how robust the overall structural change strategy of the organization is and how well the leadership program integrates with it. |

| Intervention-Driven Leadership Approach | Average to Strong with variance based on the specific organizations’ capacities, but would tend toward Strong since the learning is practically applied in real time. | Strong since the teams would be built for a specific purpose, the people involved would be selected for their commitment to the shared goal and likely to stay committed over time. | Strong since the program is focused specifically around strategic structural intervention points. |

Section 06

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation is striving to build a national Culture of Health that will enable all to live longer, healthier lives now and for generations to come, with a strong focus on dismantling structural racism in the U.S. health system . The goal of RWJF’s leadership investments is to ensure that leaders in every community work inclusively so that everyone has a fair and just opportunity for health and well-being.

For 50 years, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has operated a powerful leadership development program, Clinical Scholars, possibly the longest-running and most influential clinical leadership program in the country for advancing health equity. Many leaders in healthcare today attribute at least part of their success as leaders to the Clinical Scholars program.

Yet even with recognition of the program’s benefits to leaders, there was a growing sense within RWJF that an expanded approach to leadership is now needed. That recognition is based on RWJF’s deepened commitment to dismantling structural racism in the health system and a growing recognition that this large, complex, and deeply embedded structural challenge requires more diverse groups of people leading together in new ways.

As the researchers talked with 61 leaders, patient advocates, and patients themselves across the health system (and consulted in open sessions with hundreds more stakeholders), it became clear that funders need fundamental shifts in their thinking about leadership.

This website contains the key learning from that journey of discovery about what kind of leadership we need to achieve this audacious goal. need to dismantle structural racism in the U.S. health system. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation is just beginning to dig into what these learnings, and to have conversations about what their role should and can be going forward. This challenge is daunting, but we know facing it head-on is now more crucial than ever. We hope that other funders focused on leadership for social change will reflect and act on these learnings, as well.

Heather Equinoss, Consultant

Issac Carter, Consultant

Karen Proctor, Strategic Advisor

Luzette Jaimes, Consultant

Melissa Darnell, Project Manager

Russ Gaskin, Lead Consultant

Sharon A. Simms, Consultant

Tema Okun, Strategic Advisor

Aletha Maybank, MD, MPH, Chief Health Equity Officer, SVP, American Medical Association

David Ansell, MD, MPH, SVP for Community Health Equity, Rush University Medical Center

Linda Burnes Bolton, DrPH, RN, Senior VP and Chief Health Equity Officer, Cedars Sinai

Michellene Davis, Esq, President and CEO, National Medical Fellowships

Somava Saha, MD, MS, Executive Lead, Well-being and Equity (WE) in the World

Theresa Trujillo, Co-Directora Executiva, Center for Health Progress

In order to ground our inquiry in the lived experiences of people within and around the health system

, CoCreative conducted 61 in-depth interviews with health system stakeholders, both those who most impact health outcomes and those who are most impacted by disparate outcomes based on race.

The stakeholders were from rural, Indigenous, urban, and suburban communities, and represented a diversity of racial and ethnic identities. Of the people interviewed, 75% self-identified as female, reflecting the heavy representation of women in the health sector2. Interviews were conducted virtually via Zoom. Each lasted from 60 to 90 minutes and sessions were recorded and transcribed to ensure accuracy. The stakeholders included:

The interviewees included 8 clinicians who had participated in, or are currently participating in, RWJF leadership programs.

Some interviews, such as those conducted with patients about their experiences with racism, used an empathy interview format, in which we focused less on analysis of the system and more on their direct experiences, how those experiences impacted them, what meaning they made from those experiences, and how they responded. Other interviews used a “system dynamics” interview format, in which we asked people to consider how and where structural racism is showing up in the U.S. health system and what resources, opportunities, and barriers they see to dismantling it.

The research team held six consultation sessions with an additional 150 health system stakeholders and patients. In these sessions, which were open to any interested person and promoted through social media and RWJF’s network, participants shared their feedback on the emerging analysis of structural racism , their hopes and aspirations for an equitable health system , and their recommendations for where to focus structural work for the greatest impact. Along with the interviewees, their insights and feedback on our landscape analysis and program pathways are reflected throughout this report.

Additionally, the project team formed a six-person Advisory Team to challenge and guide thinking on the project approach, assumptions, and learning along the way. The Advisory Team served as the core focus group for testing and refining the project framework and, most importantly, provided framing of both the issues of structural racism in the health system and an articulation of the system we need and want.

CoCreative began interviewing health stakeholders in late August 2021 and concluded the interviews in mid-December 2021.

The stakeholder consultation sessions were timed for key intervals in the research process when the insights and feedback from those meetings could most powerfully inform the emerging analysis of the U.S. health system, identify and prioritize structural intervention points, co-create a vision for the kind of leadership that is needed to achieve our goals, and shape the possible program pathways found in our final recommendations.

We offered a $75 honorarium to each interviewee as well as anyone who attended each stakeholder consultation session.

To guide our inquiry about the challenge of structural racism in healthcare and effective practice in the healthcare and leadership development fields around structural racism , CoCreative developed and utilized interview guides specific to stakeholder segments:

This consultation process allowed us to develop a shared picture of the role structural racism has played and continues to play in the U.S. health system, collect insight on where the most powerful intervention points might be, and understand how health system leaders are experiencing the system around them. Our empathy interviews with patients and patient advocates grounded the analysis and program pathway design in real human experiences and complemented our systems perspective. We shared, socialized, tested and shaped our project goal, definitions, analysis and recommendations with others, expanding our circle of connections over time to build growing alignment about the why, who, what and how of this project.

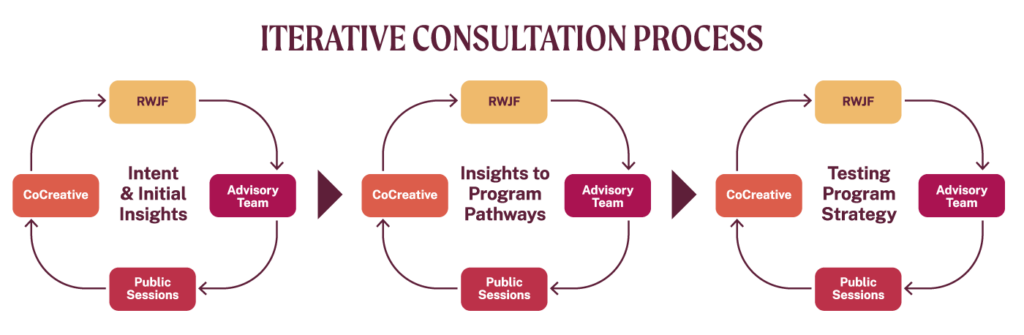

What made this process unique was its iterative design and ongoing consultative process that involved the CoCreative consulting team, RWJF, the project Advisory Team, and public stakeholder sessions. At every point we tested and refined the emerging thinking and analysis, incorporating the insights and feedback of everyone in every cycle.

We recognize that the work to understand and address systemic racism is ongoing and continually finds its source in the experiences, perspectives, and labor of Black, Indigenous, and people of color. Countless individuals and groups, over generations, have dedicated their lives to the pursuit of equity. We wish to honor the legacy of their work.

We are grateful to the 61 people we interviewed who contributed their wisdom, shared their aspirations, and spoke their truths about how structural racism manifests itself within the health system and what it will take to dismantle it.

We appreciate the work of the Advisory Team members—Theresa Trujillo, Dr. Somava Saha, Michellene Davis, Dr. Linda Burnes Bolton, Dr. David Ansell, and Dr. Aletha Maybank—for informing and refining the project intent, the definitions of key terms used throughout the project, the landscape analysis, the leadership program strategy and design, and for their own courageous leadership to bring forward a more equitable health system.

We thank Dr. Miraj Desai for sharing his research, advice, and consultation on the emerging insights from the field.

We are grateful for the collaboration of David Peter Stroh in developing the system maps to analyze systemic racism within the health system.

Finally, we thank the 150 people who attended stakeholder consultations sessions to co-design the collective leadership program.